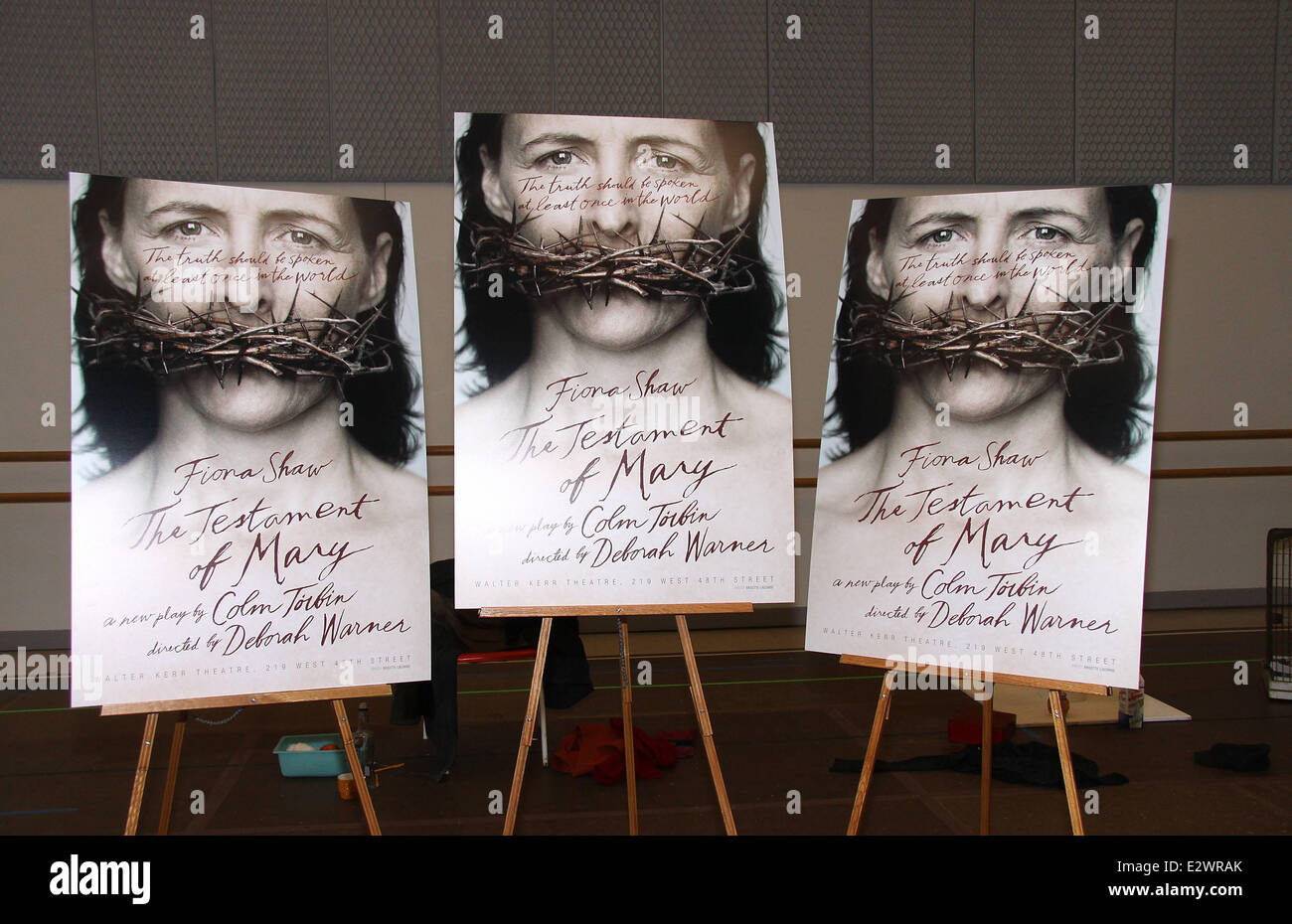

It is all distraction, as if the raw power of the work is not sufficient to hold the attention of the audience, as if Shaw is not capable of maintaining the attention of a full house for 80 minutes. What Warner does is to try to impress the audience with tricks – costume changes, a tree that doubles for the cross of crucifixion (and actually is quite lovely, suspended as it is above the ground, tantalisingly out of reach of expectations), screens that move up and down and across and from which light reflects or shines or changes colour, chairs, a pool of water into which the suddenly naked Shaw immerses herself a la baptism, a cage for the absent vulture, a ladder, a table and other detritus. This is the clutter of props and furniture, lovingly arranged by Tom Pye, none of which does anything really to illuminate the text, but all of which gets in the way of Shaw’s performance. Who would have thought that in a live theatrical production the response of the audience would have played a significant role?Įveryone who has ever performed in or directed a play.īut back to Warner’s “extraordinary landscape and dreamscape”. In case you are interested, it turns out that that surprising further dynamic is – the audience. But I think we would both say there is a further dynamic to this feeling of community.” Apart from her pre-show feathered friend – the vulture, she is supported by an extraordinary landscape and soundscape – which bring layers of presence and life to the dreamscape within which she plays. “ When asked what it is like being alone on stage, Fiona replies that she is not really alone in Testament. Yes, it really is as ham-fisted and clunky as it sounds. This all seems to suggest a notion of “picking over bones”, a thought re-inforced by the disappearance of said vulture when the text comes into play and the first image when the lights go up: Ms Shaw producing two dry bones from within her garment. Then Ms Shaw enters the stage with a huge vulture on one hand and walks among the audience. Proceedings commence by the audience being invited onto the stage where they can meander around the various props and pieces of furniture. Indeed, Warner ‘s production makes the best case possible for Toíbín’s words to be read or merely heard the reader’s or listener’s imagination can conjure more relevant and pertinent possibilities than Warner manages here. It would, no doubt, be a powerful radio play. Of course, it is not a simple version Toíbín laces the narrative with unexpected events, thoughts and feelings, thereby commenting on faith, feminism and modern preoccupations while also dealing with Lazarus, the crucifixion, the resurrection and other central tenets of Christianity. The simple conceit is to tell many of the high points of Christ’s life from the point of view of his mother, a woman who, like so many others, sacrificed her life and happiness for her child. Toíbín writes with skill and deftness some of the passages here are wonderfully evocative, almost magical in their range and beauty. Toíbín wrote the piece first as a monologue, then a novella (listed for the Booker Prize) and then Warner and Shaw took their collaboration to Broadway and from there to the Barbican. I mention this because, startlingly, that revelation is really the only one the production has to offer. Well, at least she does for this production, which is a “solo show” that is a collaboration between Shaw and Warner, the text of which is written by Colm Toíbín. One of the great mysteries, one of the burning imperatives of our time, one of the most thought-provoking and much discussed controversial topics of modern life is solved, uncovered and illuminated by Deborah Warner’s production of The Testament of Mary, now playing at the Barbican Theatre.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)